Animal Species in the Harrison Collection

By Kirsty Graham

Colonel James Jonathon Harrison's hunting expeditions took him around the world in search of unusual and large specimens to add to his collection of animal trophies. His hoard was extensive and his activities prolific enough to draw comments from his fellow hunter Percy Powell-Cotton, the renowned taxidermists Rowland Ward and from Scarborough Corporation on being gifted the collection initially. At the time, most of the walls at Brandesburton Hall was festooned with examples of animal parts.

This page provides a list of species which can be attributed to the Harrison Collection.

DESCRIPTIONS

Bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus) from Abyssinia 1899 © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus)

IUCN Red List: Least Concern, stable

Size: 0.5-1m tall Weight: 25-80kg

The bushbuck is a species of antelope that lives in ~40 African countries. This specimen was hunted during JJ Harrison’s expedition “through the Hawash valley to Lake Rudolf” (Harrison 1901). Harrison travelled with a surveyor and a taxidermist to record the expedition and preserve his hunting trophies. His diaries report that he hunted another bushbuck in 1900 and four more in 1904.

Visit the African Wildlife Foundation to learn more about bushbucks!

Grant’s Gazelle from the Harrison Collection © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Grant's gazelle (Gazella granti) Trophy head from Lake Rudolph, 1900.

IUCN Red List: Least Concern, decreasing

Size: 1.4-1.7m long Weight: 45-65kg

The Grant’s gazelle, named for Scottish colonialist James Augustus Grant (1827-92), lives in East Africa and includes three subspecies. As well as collecting trophies like this one, JJ Harrison’s expedition also ate Grant’s gazelles, among other species: “Luckily, our camp was among countless herds of game -- hartebeest, Grant's and reed bucks chiefly -- so we had no need to consume our stores.” Throughout Harrison’s diaries, he reports shooting no less than 15 Grant’s gazelles, making them one of his most hunted species.

Visit the African Wildlife Foundation to learn more about Grant’s gazelle!

Trophy head from Lake Rudolph, 1900. © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Thomson's gazelle (Gazella thomsonii)

IUCN Red List: Least Concern, decreasing

Size: 55-82cm tall Weight: 15-35kg

This gazelle is named for another British colonialist Joseph Thompson (1858-1895), who late in life was employed by Cecil Rhodes to secure treaties and mining concessions on behalf of the British South Africa Company. Despite popular imagination, “explorers” like Thompson and Harrison were rarely engaged exclusively in naturalist and geographical research – they were a central part of European colonial expansion. There doesn’t seem to be a reference to the Thomson’s gazelle in Harrison’s diaries, but another gazelle – Clarke’s gazelle, now more commonly called ‘dibatag’ – featured several times. Unsurprisingly, Clarke’s gazelle also got its name from an English colonial administrator (and known racist and antisemite), George S. Clarke. The way species have been named is inextricable from a history of trophy hunting and colonialism.

Visit the African Wildlife Foundation to learn more about Thomson’s gazelle!

Guereza colobus (Colobus guereza) © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Guereza or white mantled colobus (Colobus guereza).

IUCN Red List: Least Concern, decreasing

Size: Up to 75cm long Weight: 4-14kg

These beautiful monkeys are hunted by leopards, eagles, chimpanzees, and humans. Colobus are found in at least 15 countries in Africa, and this specimen was hunted in the Congo Free State, 1904. The Congo Free State covered the entirety of today’s Democratic Republic of the Congo, and was privately owned and exploited by King Leopold II of Belgium. Colobus monkeys have black fur with long white tufts growing from their sides, their so-called ‘mantle’. This fur has long made them attractive for hunters, but their current biggest threat (as with many animal species worldwide) is habitat loss.

Visit the African Wildlife Foundation to learn more about colobus monkeys!

--

Gerenuk (Litocranius walleri) from Lake Rudolph. 1900 © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Gerenuk (Litocranius walleri) from Lake Rudolph. 1900.

IUCN Red List: Near Threatened, decreasing

Size: 140-160cm Weight: 29-58kg

There does not seem to be a reference to the gerenuk in Harrison’s diaries, but perhaps he called it by another name. Like the dibatag (formerly Clarke’s gazelle), the gerenuk is now most commonly called by its Somali name. Renaming species (like renaming places) is a decolonial practice. “Gerenuk” means “giraffe-necked” in Somali, and these long-necked antelopes certainly live up to their name. The gerenuk’s long neck allows them to feed on higher leaves than many other gazelles and antelopes.

Visit the African Wildlife Foundation to learn more about gerenuk!

Harrison's pygmy antelope (Hylarnus harrisoni or Nesotragus Batesi) © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Harrison's pygmy antelope (Hylarnus harrisoni or Nesotragus Batesi) Holotype.

IUCN Red List: Least Concern, unknown

There is some controversy about the classification of this species of antelope, but it’s most commonly referred to as Bates’ pygmy antelope. This species was named after the American naturalist George Latimer Bates with Harrison’s Pygmy Antelope now considered to be the western subspecies of Bates’ Pygmy Antelope, Nesotragus batesi harrisoni. The way that we name species ‘scientifically’ can be contentious. The ‘discoverer’ picks the name and local names are rarely used (but see Gerenuk and Dibatag). Assigning species is not straightforward, and species are regularly recategorized. Bates’ pygmy antelope was recently reassigned from the genus Neotragus to Nesotragus to reflect its closer relatedness to impala than to duikers. The way that scientists can recategorize species might be a hopeful indicator that we can change their old colonial names as well!

--

Oribi (Ourebia ourebi) trophy head from Abyssinia 1889 © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Oribi (Ourebia ourebi) trophy head from Abyssinia 1889.

IUCN Red List: Least Concern, decreasing

Height: 50-67cm at shoulders Weight: 12-22kg

Oribi is a species of antelope found in a wide range of savannah and other grassy habitats. Depending on their habitat, they have different mating systems, which is unusual for antelopes. Harrison’s journals document shooting no less than 25 oribi – his most hunted species! Oribi have a really wide distribution, across western, eastern, and southern Africa. The name is derived from their Afrikaans name, ‘oorbietjie’, so while not named after a colonialist it comes from a colonial language. Other Afrikaans species names that you might recognise include wildebeest, springbok, steenbok, aardvark, and duiker.

Duiker sp. (Cephalophinae) © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Duiker sp. (Cephalophinae)

IUCN Red List

There are over twenty species of duiker (another Afrikaans name), a subfamily of small antelope, but Harrison doesn’t often specify in his diaries. He hunted around 15 duikers throughout the diaries, and the only species that he refers to is the red duiker in Mozambique. Red duikers are around half a metre tall and weigh about 15kg. They live in forests and denser vegetation, so the loss of these types of habitat are a threat to them.

Aardvark (Orycteropus afer) © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Aardvark (Orycteropus afer)

IUCN Red List: Least Concern, unknown

Size: 105-130cm Weight: 60-80kg

Like oribi, aardvark also comes from Afrikaans and means “earth pig”. These are burrowing nocturnal animals, so are very hard to spot. Aardvarks are widely distributed across Africa, and they are bigger than you might expect! Their size and weight overlaps with the range for Leopards! Harrison’s diaries don’t include where or how he acquired this specimen. Aardvarks eat mainly ants and termites, but also have a symbiotic relationship with the ‘aardvark cucumber’, a subterranean fruit that grows in their burrows.

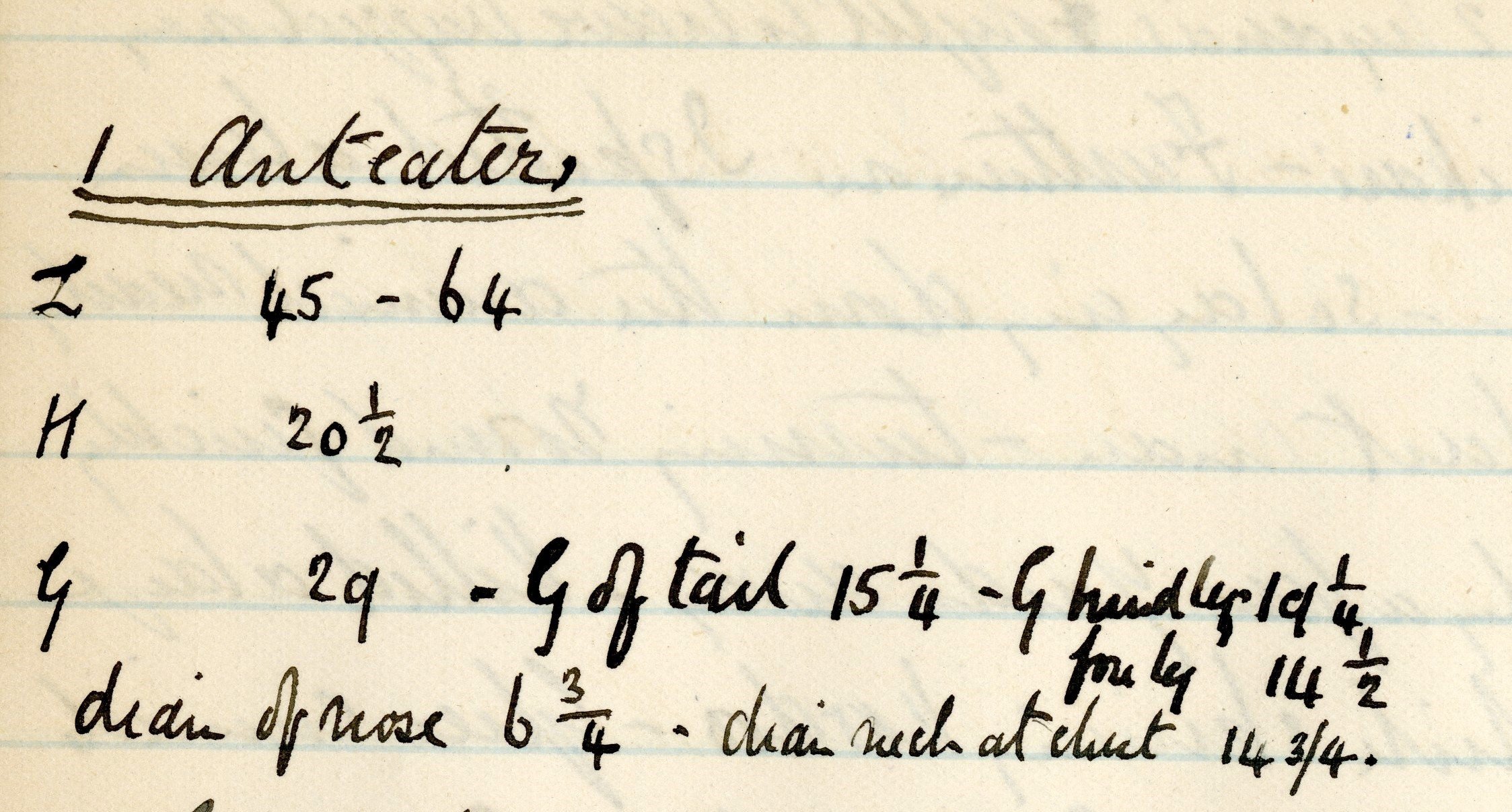

In the Harrison Africa diaries there are 3 references to ‘ant eaters’.

2nd December 1899 Harrison Diaries © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

“I turned off to hunt along the foot hills; after 3 miles spooring lesser koodoo I suddenly saw a tail sticking out of a large hole in ant heap. Seeing some animal I got my shikaree to push in a stick, further in at a side hole, when out came an ant eater which I promptly shot - a wonderful bit of luck, as very few people have ever seen them, much less shot them.”

2nd December 1899 Harrison Diaries © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

These dimensions match those of the animal labelled as ‘? Ant eater’ in the Scarborough Museums Trust Collection. The museum animal matches the general descriptions of an aardvark, including the fact that it only has 4 toes on the front feet.

Harrisons second description of an ‘ant eater’ is found in his 1908 diaries when he returned to the Ituri Forest area

17th February 1908 Harrison Diaries © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

“Did not get up till late as we intended staying in camp all day to await Com. Eugh who arrived at 3.30 with thirty soldiers and a large retinue. On his advice we sent the two pair of tusks into Irumu and I shall ask for them on landing in Hamburgh. During the day I got a curious beast, with very long tail and tongue covered with big scales. It took us some time to kill as it seemed to thrive on poisons. We had our usual evening moonlight visit from a huge one tusker.”

This description is more suggestive of a pangolin. Pangolin are covered in keratinous scales and are known to reside within the Ituri Forest region.

“Up at sunrise and did a short cut to Leese, 2 ½ hours. Got a specimen of the long tailed anteater or armadillo. About teatime we got our English mail; three lots of papers, sent on by Mr. Van Marcke, who sleeps next camp.”

There is no species of ant eater known as ‘long tailed’. There is however a species of pangolin known as a long-tailed pangolin (Phataginus tetradactyla), which is resident in the Congo basin. Armadillo are only native to the ‘Americas’. Once again, the description provided by Harrison does not match the specimen in the museum collection

4th February 1909 Harrison Diaries © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

About the author

Dr Kirsty E. Graham - is a Research Fellow at the University of St Andrews’ School of Psychology and Neuroscience. Dr Graham’s research examines how great apes use gestures to communicate, and they have spent a lot of time studying bonobos in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

REFERENCES:

Harrison, J. J. (1901). A journey from Zeila to Lake Rudolf. The Geographical Journal, 18(3), 258-275.