A Brief Introduction To The Congo

By C Goode

The Congo is located in central Africa and its geography is dominated by the river of the same name. The people have been described as ‘rich in language, music and deeply honoured traditions’ [1], as well as with their art with over 200 ethnic groups and 400 languages and dialects. Before the Portuguese arrived in the late fifteenth century the Congo region was unknown and untapped. The majority of its history has been written by the colonisers, white Europeans or Americans so the voice of the Congolese has been muted. There are some exceptions to this such as King Affonso and George Washington Williams.

Coat of arms of the Free State of Congo (1886) Image in public domain

The Portuguese were not the first group to exploit the Congo’s people, selling them at first in Brazil, then in North America from the early sixteenth century. It was not just the value of the people that sparked the economic interest in the Congo but the array of raw materials.

“The Founders of the Congo State” from the top King Leopold II of Belgium, the Prince of Bismark, and Henry M Stanley

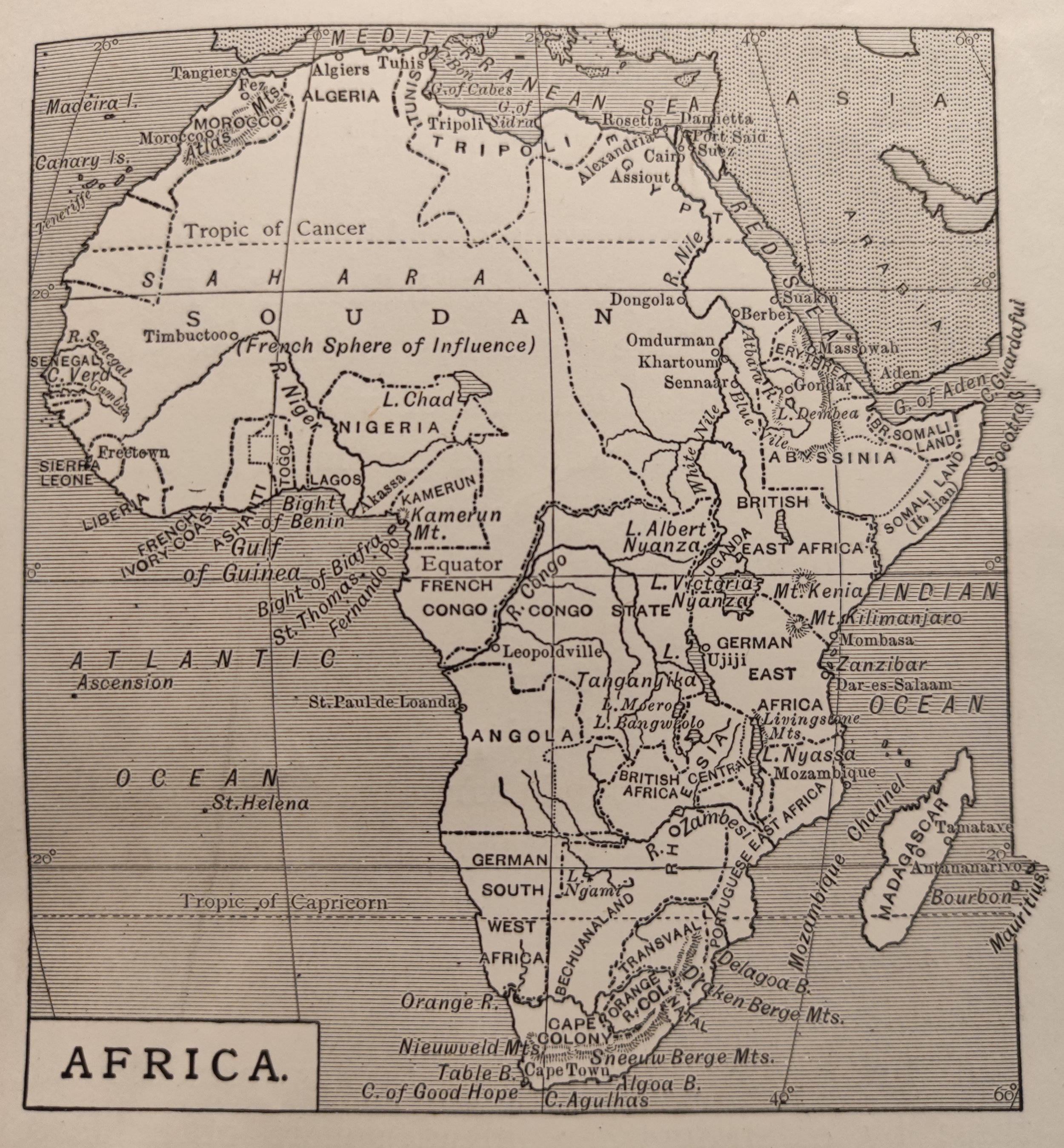

In 1885 when King Leopold established the Etat Independence du Congo (the Congo ‘Free’ State) it was seventy six times larger than Belgium and would fit in the area between Zurich, Moscow and central Turkey. Leopold wanted ‘a slice of this magnificent cake’ and to take its ivory, rubber and other valuable resources. Earlier in the nineteenth century the European powers had carved up Africa between them, with little regard for the wishes of the African people.

Belgium became independent in 1830 and joined the scramble for Africa later than the other powers. Leopold did his detailed research and made contact with those who might help this quest to open up the Congo region. One such person was Stanley, who Kingsolver described as ‘the vainglorious explorer’ [2]; his real name, on his birth certificate, was John Rawlinson bastard. He brutally used the Congolese porters on his expeditions. Ironically Leopold was praised for his patronage of Christian missionaries and his ‘humanitarianism’; he set up a Commission for the Protection of Natives.

Leopold created treaties with the tribe leaders and misrepresented how trade would be conducted and thus importantly getting the recognition of the USA. Bismarck, the Chancellor of Germany, was more astute and referred to Leopold’s plans as ‘fantasies’ [3]. By a series of deals, alliances and manipulation Leopold was able to enrich himself and make the Belgian Congo his own private property. Adam Hochschild’s sub-heading to his book, King Leopold’s Ghost, is ‘a story of greed, terror and heroism’. The terror and brutality was supplied by the Force Republique; there was no free trade and Morel spoke of ‘the theft of African land and labour’ [4]. In contrast, generations of Belgian children were taught about their country’s positive contribution to the Congo in terms of education, healthcare and civilisation!

Morel was a superb speaker and organised many meetings to expose the horrors of crimes committed against the Congolese people. His Congo Reform Organisation, meant that by 1908 international pressure highlighted the injustices to the world. Those killed, through murder, starvation, exhaustion and exposure to disease, amounted to ten million Congolese people, half the population.

George Washington Williams, 1889, image in public domain

A contemporary of mine, whilst at school in Hull in the 1980s was taught about the Belgian exploitation of the Congo but for many the horrors committed by Leopold and the Force Republique remain little known. The voice of the colonisers dominates, with scant room for the Congolese people. George Washington Williams, a black US journalist and historian, was one of the first visitors to the Congo who published the truth, in which he stated that he wanted ‘local not European government’ [5].

Leopold died in December 1909, but it was not until 1930 that forced labour was abolished in the Belgian Congo. In the aftermath of the Second World War and global moves towards decolonisation, nationalist movements in Congo developed. Independence came on 30th June 1960, following an election which Belgium had sanctioned. Patrice Lumumba became its first prime minister and he demanded not just political but economic independence. Support from the Soviet Union rang alarm bells for the western corporations and the US government. The latter wanted to protect their investments in the mining of copper, diamonds, cobalt, tin, gold, manganese and zinc. The USA, Belgium and Mobutu (Chief of the Congolese army) were responsible for Lumumba’s assassination, enabling Mobutu to take his place, and rule Congo (renamed Zaire in 1971) from 1965 to 1997. Hothschild highlights a number of similarities between Mobutu and Leopold, in that they both enriched themselves and ruled autocratically [6].

About the author

C Goode - is a local researcher based in Scarborough

References

Hothschild, A. (2019) King Leopold’s Ghost,

p. xiii introduction by B. Kingsolver

Ibid p.58

Ibid p.83

Ibid p.306

Ibid p. 111

Ibid p.301