Burr Bank, Cuddy Rood & Bawdy Bank

A Focus on the Scarborough Fishing Community 1880-1910

By Keith Barley

Article from Shields Daily Gazette, Thursday 20 August 1885, describing the loss of Charles Barley

Today, looking down from Burr Bank terrace (earlier known as Cuddy Rood with its inference of St. Cuthbert and the much earlier name of Bawdy Bank) it is a derelict grassy slope, which declines down toward Quay Street past its former yards and on to the Harbour. In the east it is defined by Dog and Duck Steps and in the west, Long Greece, (‘Gresse’ Old Norse for steps). Here in 1880 was the huge Ice House containing the expensive ice imported from Scandinavia for preserving fish on boats, stored in wood shavings until needed. Within this area of higgledy-piggledy rows of various pan tiled dwellings in dark narrow streets, large fishing families sheltered tip-to-toe with each other in simple rented dwellings. One such family of seven, were the Schofield’s who in 1891 had moved north from the Hessle Road fishing community in Hull to Scarborough. Annie had already lost her first husband Charles Barley in 1885 whilst fleet trawling off Heligoland on the SV Parthenhope.

Ordinance Survey map 25inch 1892-1914 with Burr Bank highlighted [1]

Born in Beverley in 1840 and with little formal education, she became a domestic servant, as was her mother and in time her daughters after her. In 1891, Annie was married to George Schofield, another fisherman, and living at 1 Burr Bank with 6 daughters, two sons having already left home. George was away for long periods and Annie appears as ‘Head’ of house on the 1891 census. The place they lived is impossible to locate now with reliability of house numbering being twice revised by the town council and the area being demolished in 1967.

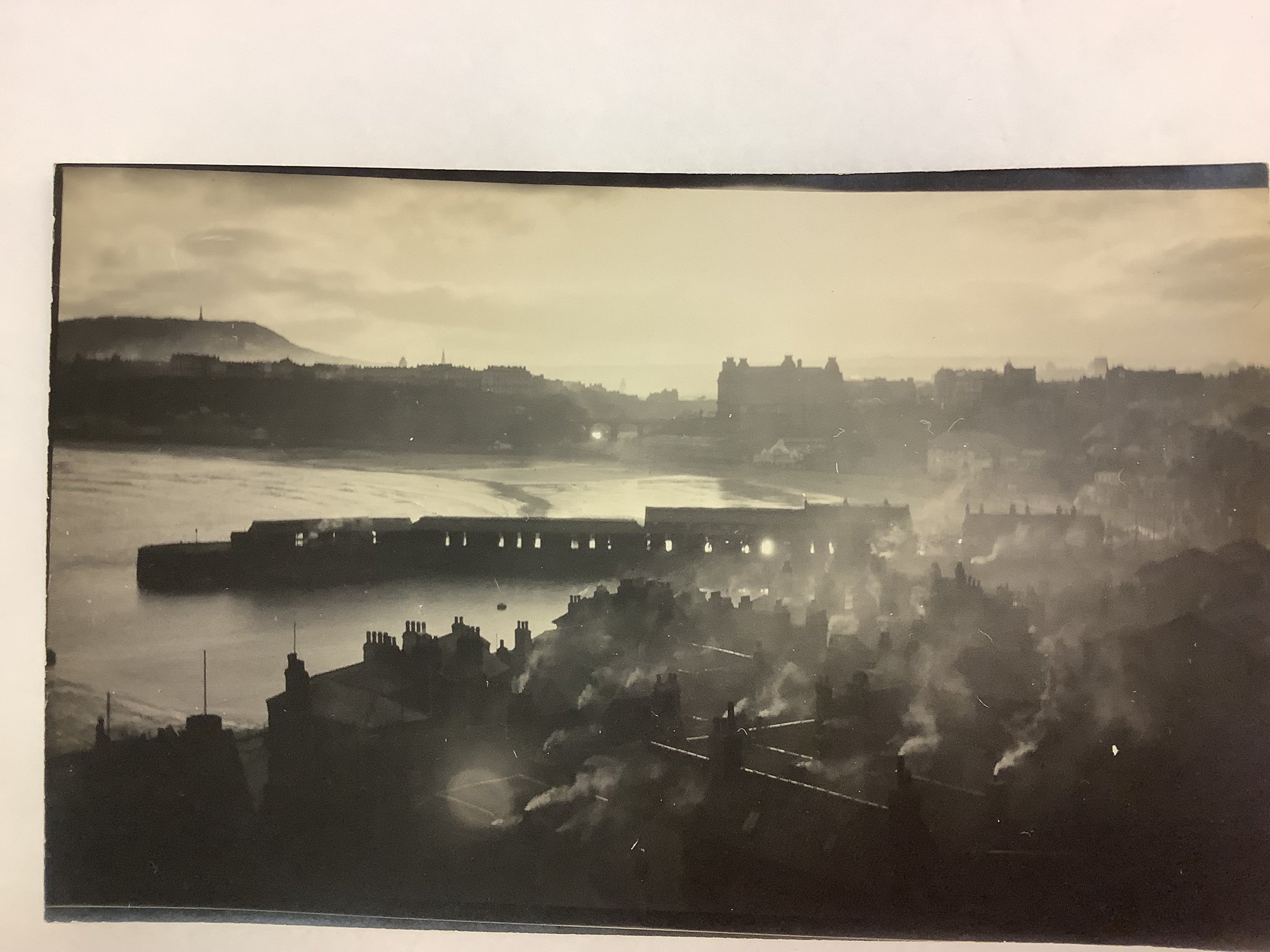

Sandside (1900) © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

The York and Scarborough railway provided access to national fish markets and boom years in fishing followed but by 1890 inshore trawling had been banned and fishermen were forced to risk using illegal nets to make a living. The industry was in decline having reached its peak in 1881 when 1,632 fishermen were counted. Eighteen years later that number had fallen to 1,181 including many part-timers. Despite this fishing did continue to increase briefly but the pace of expansion combined with the lack of responsible conservation measures meant that many fishing grounds became denuded. Rich catches of cod, ling, haddock, whiting, plaice, sole and skate were now becoming much less available and crews were having to work harder and sail further for longer in all kinds of weather and risk to maintain catch levels. Crew livings became much reduced and weekly wages were often no more than 15-20 shillings a week.

Article from Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Friday 11th August 1899

Although crew hands incurred no risk to their wages, neither did they share in any bonus, unlike the owner, skipper or mate. On a haul worth £40 owners would claim up to 60% of that figure. What was left was then distributed between skipper and mate, leaving the crew hands pressurised by owners to contribute towards the cost of power winches and capstans to aid fishing. Fishermen started looking at other ways for income without the effort of embarking long voyages away from home for diminishing returns. Some enticed the public for short sea trips or boat rides. Here we can see George working in South bay near the Spa, hired by a gentleman, Mr.J.M. Robertson of The Esplanade to help him catch salmon . However an astute Fishery Board officer found them to be without a license and using illegal netting. The gentleman was prosecuted and fined but merely being his assistant, George avoided prosecution or penalty and the heavy fine of £10, (10 weeks wages for George) plus costs, was borne by his client.

Children in a Scarborough alleyway, 1878, © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

In a climate of poverty the children of Burr Bank in the late nineteenth century didn’t have an easy life either. They often had no shoes on their feet and the concept of pocket money was alien. Parents worked hard to put food on the table, but there wasn’t much surplus for treats. However it seems that around Easter for a month when the herring fleets came to Scarborough children could make some money. Herring boxes were so full when offloaded onto the harbour wharves they could not always contain the fish and the herring would spill out. Then children would wait and watch and even coax the odd herring out so that they fell onto the ground where the fish were deftly appropriated and claimed as ‘spoils’. The children would then run off and sell their gains for pennies amongst the nearby dwellings too fast to be caught and receive a ‘clip. But then there would be those who would look on, smile and understand.

About the author

Keith Barley - was born in the Hessle Road Fishing Community, Hull and is now retired after a career in International Exhibition & Interior Design. Life long interests around Drawing and Art allowed him to pursue his passion for an MA Fine Art at Sheffield Hallam University (2011). He is also a proud father and grandfather after being married 46 years. His interests now include Painting, Printmaking, Photography and some Writing together with Mindfulness Meditation. He is learning to play Irish Tenor Banjo and Tenor Ukelele . His research interests include local, social and maritime histories of Scarborough and Hull as well as his geneology.

References