Colonialism and Exploitation

By Lynn Crosby

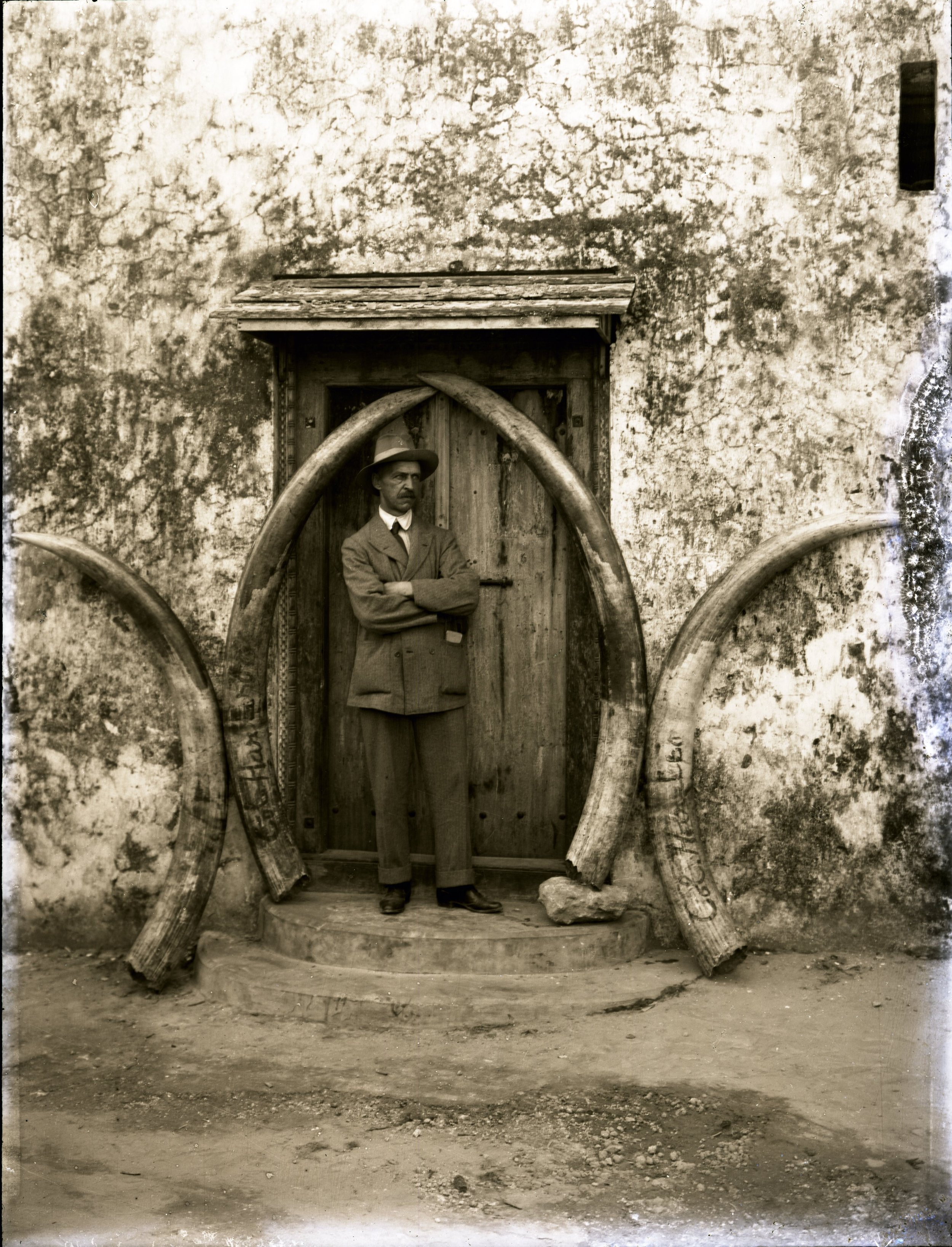

Photograph from Harrison’s album © Scarborough Museums & Galleries

The myth of the Europeans as a civilising influence on the peoples of Africa provided the justification for the exploitation of that continent, its resources and its peoples, during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Big game hunters like Harrison had no qualms about taking what they wanted, exploiting the labour of indigenous people to service their needs whilst on their expeditions, killing any animals and birds they wanted and bringing their trophies home. It was in this spirit that Harrison “persuaded” the Bambuti people to come to England, as objects of curiosity, performing to entertain the British public, divorced from their cultural context. Similarly British museums, influenced by imperialist and attitudes of racial superiority, have felt entitled to acquire and display items looted from other countries as in the case of the Harrison collection.

Even many of those who opposed Harrison's bringing the Bambuti to England for the purpose of exhibiting them, believed in the superiority of British culture and attitudes were, at best, paternalistic. Lord Lansdowne's intervention when the expedition stopped off in Cairo does seem to have been motivated by concern for their health and welfare, but how much agency they were granted in, not only the decision whether or not to come to Britain, but also being subjected to medical examinations, remains unclear.

Article from Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer , Saturday April 22nd 1905

The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, in questioning the ethics of the enterprise, reflect an attitude of cultural and moral superiority. In its report concern was expressed that the experience of twentieth century civilisation might have an unsettling effect on the Bambuti and that although, “Old prejudices and ancient fears might be dissipated and the civilising influences of Western world be carried to a people almost living as primeval man lived”, the Bambuti might be influenced by some of the vices of Londoners. The British view articulated here suggests the prejudices and fears of the British towards these indigenous cultures might be alleviated by their encounters with the Bambuti and spreading our Western ways is an improving experience for them, however, the writer worried that, having seen the wonders of Western civilisation, they might not be happy to return to their old way of life, believing that their way of life was less desirable.

Mounted duiker head © Scarborough Museums & Galleries

The earlier exhibitions of the Harrison collection emphasized his role as a big game hunter and explorer, exhibiting some of the trophies from his travels and photographs of the Bambuti people in British Victorian dress. As the museum's emphasis changed over time to reflect local natural history the collection was relegated to the cellars gathering dust. The present exhibition has a very different focus from the original, looking at the collection in the context of imperialism and introducing new perspectives. The Local to Global project brought in a consultant specialising in advising on the decolonisation of museums and also involved Congolese people. A decision has been taken not to show photos of the Bambuti people taken whilst they were in Britain, rather the Bambuti people themselves have been given a voice in a film which shows some of them talking about their culture and present day challenges, many rooted in the imperial legacy.

The Scarborough News report on the exhibition reflected the change in attitudes having talked to the museum's curator, it reported, “Citizen researchers from Scarborough and beyond, members of the Congolese diaspora in the UK , Bambuti people from the Ituri Forest, students, artists and activists have been introduced to the collection and made contributions to demonstrate how a collection like this can act as a springboard to explore multiple perspectives”.

It would be wrong to assume however that all of the attitudes prevalent in Victorian England, in respect of cultural superiority, have totally disappeared. There is a growing awareness of the need to address historical and present day wrongs, but not everyone in the UK agrees with this and museums need to reach out to a wider public to educate and engage in discussion. Although most of the comments posted about the exhibition are positive there have also been negative reactions. Local to Global as part of its community outreach, worked with a local primary school to produce a model of an Ituri forest in Scarborough library. This was a good way of engaging children in a fun and educational activity and giving a new perspective of a different way of life. When I went to school we were taught that the British Empire was something to be proud of and didn't question the ethics of conquering other countries to exploit their resources. Hopefully the younger generation will have a different perspective and museums will have a role in educating them to question our colonial past, and learn from its mistakes.

About the author

Lynn Crosby - grew up near Scarborough and always had an interest in history both local and global. She is particularly drawn to finding voices hidden from history.

References

Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer , Saturday April 22nd 1905

Scarborough News October 17th 2022