From Congo’s Ituri Forest To Cairo’s Kasr El-Einy

By Joann Fletcher

When Colonel James Harrison travelled through Congo Free State in 1904 in search of big game, his diaries and photographs now in the Scarborough Collection record the places and people he encountered. Chief among them were the Bambuti (Mbuti), the subject of his 1905 book ‘Life among the Pygmies of the Ituri Forest’, and whose skills in hunting and dancing, as captured in his photographs, “caused so many friends at home to ask why I could not bring some of these pygmies to England” [1].

Map of the Nile and Congo watersheds, from R. Cooper 1914, Hunting and Hunted in the Belgian Congo, London, p.260

So with plans to stage their performances back in Britain, Harrison returned to Africa and by late January 1905 had reached the Sudanese Nile-side settlement of Lado. Having gathered supplies and porters, whose thankless task was shared by 8 donkeys, a 1,000 mile 5 week trek south brought the expedition to Lake Albert. After a steep hike to the edge of the Ituri Forest, they reached the town of Irumu, where ‘an old native chief’ was living with “a young pygmy boy of 18 called Mongongu (aka ‘Bartie’), who could also talk Swahili” [2], the chief given blankets and clothes in exchange for the boy, who now rode on the lead donkey.

Image taken from Harrison’s collection © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Crossing the Ituri river and venturing deeper into the forest, Harrison describes the Bambuti men and women who came to dance and to hunt, later noting that one woman (Amuriape) had wounds “caused by a poisoned spear in a tribal fight” [3]. He also states that Bambuti men seldom reached 40 years of age and the women only 35, with all at risk from “all sorts of diseases” including smallpox, and “all alike seem to suffer from a hard, racking cough” [4]. He also saw varying degrees of malnutrition, since food was scarce during 9 months’ annual rainfall which turned the forest into a swamp.

Image taken from Harrison’s collection © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

So with the rainy season fast approaching, Harrison gathered his ‘little band of volunteers’ - the three men Chief Bokane apparently aged 35, Matuka and ‘fat boy’ Mafutiminga (aka Mafuti) aged 23 and 22 respectively, plus three women, ‘good-looking’ Kuarke aged 23 (‘called by us the princess’), war-wounded Amuriape he called ‘an ugly old lady’ at 31, and Mariala, the tallest of the group [5]. Yet progress proved ‘exceedingly trying’, since “I gave up all the donkeys, besides hammocks, for carrying our friends” [6]. He also noticed that “one of our ladies is going to have measles, a rash having come out” [7], a reference to Mariala who was escorted back, while away from the forest he “had to be most careful to travel them as much as possible out of the sun, for this knocks them over at once” [6].

On reaching the British post Wadelai where Harrison sent a telegram of progress, navigable stretches of the Nile punctuated by overland treks brought the group to Lado where they resumed their river journey north aboard the government steamer ‘Dal’ [8]. Having made it to Khartoum “without any of the pygmies being at all sick except the old woman” [9], Amuriape, she received medical attention, and having dispatched another telegram Harrison and his group resumed their journey north into Egypt.

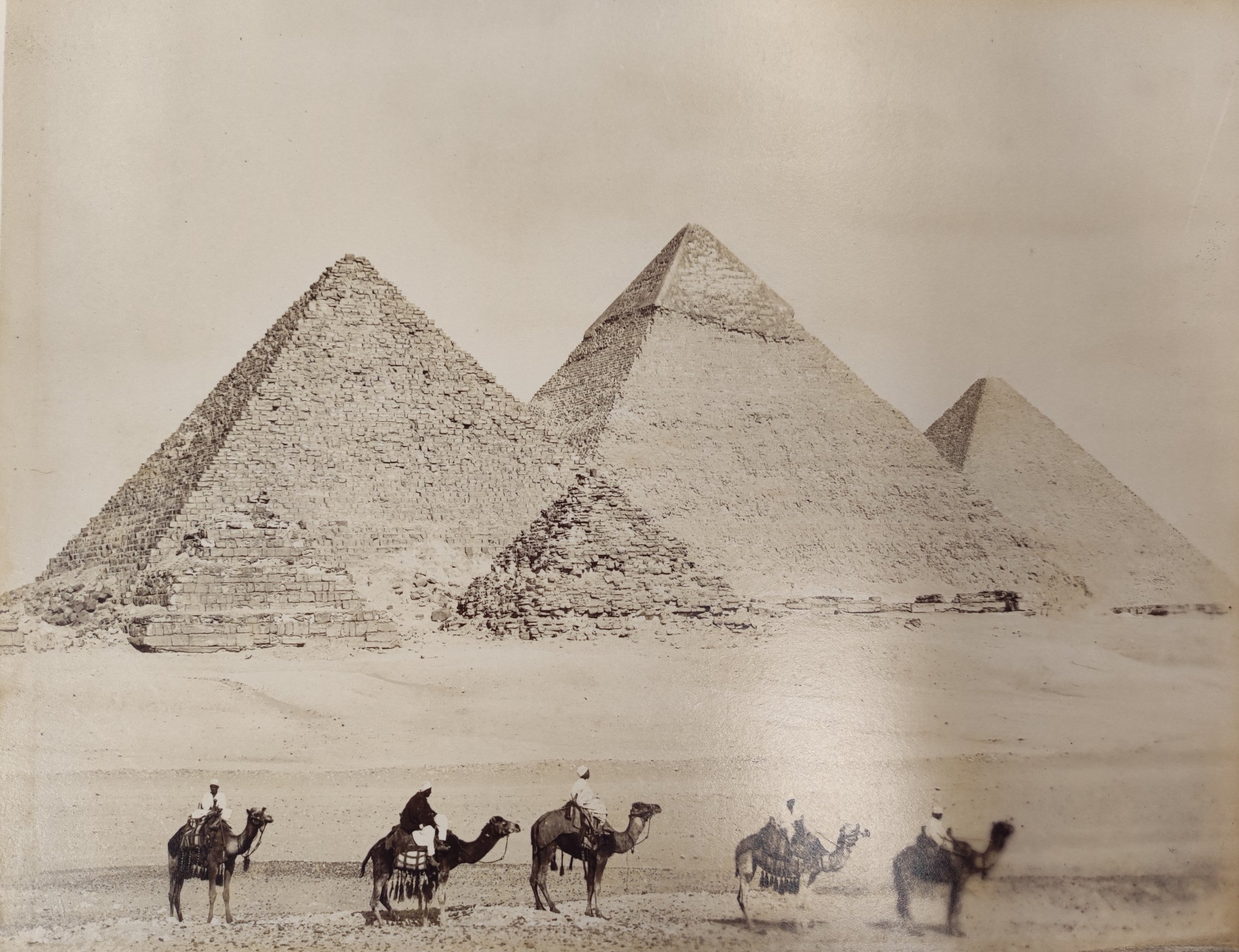

Image of Sphinx taken from Harrison’s 1891 Cairo album. Credit to © Scarborough Central Library

Finally reaching Cairo by mid-April, this lively hub of British expat society was buzzing with news of the most recent in a series of discoveries made in Luxor’s Valley of the Kings by American millionaire Theodore Davis. Best known from his photograph taken in the Valley by society photographer Sir. Benjamin Stone MP, Davis and his archaeologists had just found the gold-filled tomb of Tutankhamen’s great-grandparents Yuya and Tuya, soon attracting visits from King Edward VII’s brother Arthur, Duke of Connaught and ex-Empress Eugénie of France.

With news of what was then Egypt’s greatest archaeological discovery reported around the world, Harrison’s group were also making headlines [10] whose content raised concerns with British Foreign Secretary Lord Lansdowne. He immediately telegrammed Egypt’s British consul general Lord Cromer, asking if they were volunteers and would such a trip damage their health, which Cromer immediately investigated. For although Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire, its Turkish khedive Abbas II Helmy Bey was simply a figurehead, whereas Cromer was de facto ruler of both Egypt and the Sudan [11]. Having introduced wide-ranging health reforms, Cromer’s report for 1905 stated that “There are few countries in the world where vaccination is more efficiently performed than it is in Egypt, but unfortunately… the operation cannot be enforced among foreigners” [12], with small-pox cases that year numbering 3,979, similar numbers for measles and typhoid, plus bubonic plague fatalities reported in the Cairo press.

L-R: Chief Bokane, Matuka, Harrison and Mongongu in (possibly) Cairo, ‘The Sphere’ May 6th 1905

Cromer therefore interviewed Harrison and his group, Mongongu and Chief Bokane telling Swahili interpreters that they had “come a long way and were tired” [13] before the six were taken to Kasr-el-Aini hospital. As part of Cairo University Medical School [14] and originally a C.15th Nile-side palace appropriated by Napoleon in 1798, Kasr-el-Aini was “afterwards converted into a hospital by the French” [15] who in 1827 started a medical school on behalf of Egypt’s Ottoman Turkish ruler Mohamed Ali. When this hospital “practically became defunct ten years ago… Lord Cromer built up what is in all but name a new school of medicine” [15], where Resident Medical Officer Dr Henry Goodman examined the six.

An Egyptian felucca sail boat, taken from Harrison’s 1891 Cairo album. Credit to © Scarborough Central Library

Reporting “all suffered from slight coughs” [16], the three men were anaemic, with irregular heartbeats and enlarged spleens and livers possibly due to malaria. Estimating their ages rather lower than Harrison, Goodman added that the ‘younger woman’ was well nourished but ‘the older woman’ emaciated; also her knee was swollen ‘from an arrow wound’ (the spear wound which would soon be treated by surgery in Britain) which, combined with her curved spine, club foot and ‘feeble pulse’ presumably explained why all the group were ‘happy’ except for her. With Goodman concluding that a visit to Britain would only exacerbate the coughing and any malaria, he declared only two were fit to travel so Cromer recommended they should all be “returned to their natural home in the forests of the Congo” [16].

About the Author

Professor Joann Fletcher is based in the Department of Archaeology at the University of York. She is also Lead Ambassador for the Egypt Exploration Society, patron of Barnsley Museums and Heritage Trust, and has been researching aspects of Scarborough Museums’ collection for over 20 years.

References

Harrison, J. 1905, ‘Life among the Pygmies of the Ituri Forest, London, p.5; for term ‘Pygmy’ see Rouget, R. 2011, Musical Efficacy: Musicking to Survive - the Case of the Pygmies, Yearbook for Traditional Music 43, p.89, “May I be forgiven for using the term ‘Pygmies’, often criticized, especially in the United States, because it is stained with negative connotation. It hardly needs stated [sic] that that connotation is totally unfounded… the convenience the term offers more than makes up for its drawbacks, so I have chosen to use it”.

Harrison 1905, p.8; for Swahili as the ‘lingua franca’ of eastern Africa see Green, J. 1995, Edwardian Britain’s Forest Pygmies, History Today 45 (8) (August), p.33-39).

Harrison 1905, p.24 and Harrison’s Diary VI 6.3.05; today Bayaka women in neighbouring Central African Republic “are considered the best hunters”, Prof. Anna C. Roosevelt, Department of Anthropology, University of Illinois at Chicago, pers.comm. January 2022.

Harrison 1905, p.16 & p.24

Frontispiece in Harrison 1905 captioned “Six of the Pygmies who have come to England” although there are seven, as named in Harrison’s photo album; ‘the fat boy’, ‘good-looking lady’ ‘called by us the princess’, ‘an ugly old lady’ all in Harrison 1905, p.23.

Harrison 1905, p.23.

Harrison’s Diary VI, 19.3.05, transcribed by J. Middleton.

Film footage of Dal in 1910 transporting ‘rare specimens of fauna for the Smithsonian Institute’ at: The Government steamer Dal travels along the upper Nile River with specimens for the Smithsonian Institute and with Theodore Roosevelt Jr., in Africa, in 1910. - Stock Video Footage - Dissolve); last entry in Harrison’s Diary VI made on 1.4.05 as the Dal set sail.

Harrison 1905, p.24

eg. ‘Pigmies [sic] coming to England’, Daily Mail 15.4.05; ‘Colonel Harrison’s pigmies: an undesirable exhibition’ 6.5.05, The Daily News, in Green, J. Colonel James Harrison — From Local to Global

‘Lord Cromer and Egyptian Nationalism’ by the Egypt Exploration Society at: Tuesday Spotlight: Lord Cromer and Egyptian Nationalism | Egypt Exploration Society (ees.ac.uk)

The Earl of Cromer’s Report on Egypt for 1905, The Lancet, May 12, 1906, p.1487; plague reports in Cyr, E. 2016, Bubonic Plague in Egypt Bubonic Plague In Egypt, 1905 | Digital Egyptian Gazette (dig-eg-gaz.github.io)

see also Green, J. 1998, Black Edwardians: Black People in Britain 1901-1914, London, p.118; Bokane speaking Swahili in Green, J. 2000, ‘A Revelation in Strange Humanity’: Six Congo Pygmies in Britain 1905-1907, Africans on Stage: Studies in Ethnological Show Business (ed. B. Lindfors), Indiana, p.169.

“the largest and oldest medical institute in the Middle East” in Saleem, S.N. 2021, Egyptian Medical Civilization: from Dawn of History to Kasr Al Ainy School, Pharmacy and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Proceedings of the Conference Held in Barcelona 2018, (eds. Solà, R. et al.), Oxford, p.104-115; palace built by Ahmed Ibn Al-Ainy, grandson of Sultan Khushqadam, with various spellings eg. Al Ainy, el-Ainy, el-Einy, both Kasr and Qasr etc.

Smith, G.E., letter 6.10.00, in Dawson, W.R. ed. 1938, Sir Grafton Elliot Smith, London, p.30-31

Medical News 1898, The British Medical Journal, 2 (1,959), p.212; Green 1998, p.118.