‘When the Spirit Moved Them’: the Ituri ‘Dancers of God’ (part I)

By Joann Fletcher

In 1904 when first visiting Congo Free State, James Harrison described it as an “enormous country, reaching from the Nile to the West Coast [of Africa]” [1]. Having gone there in pursuit of big game, his focus soon shifted to Congo’s Bambuti (Mbuti) people he described in his book ‘Life among the Pygmies of the Ituri Forest’.

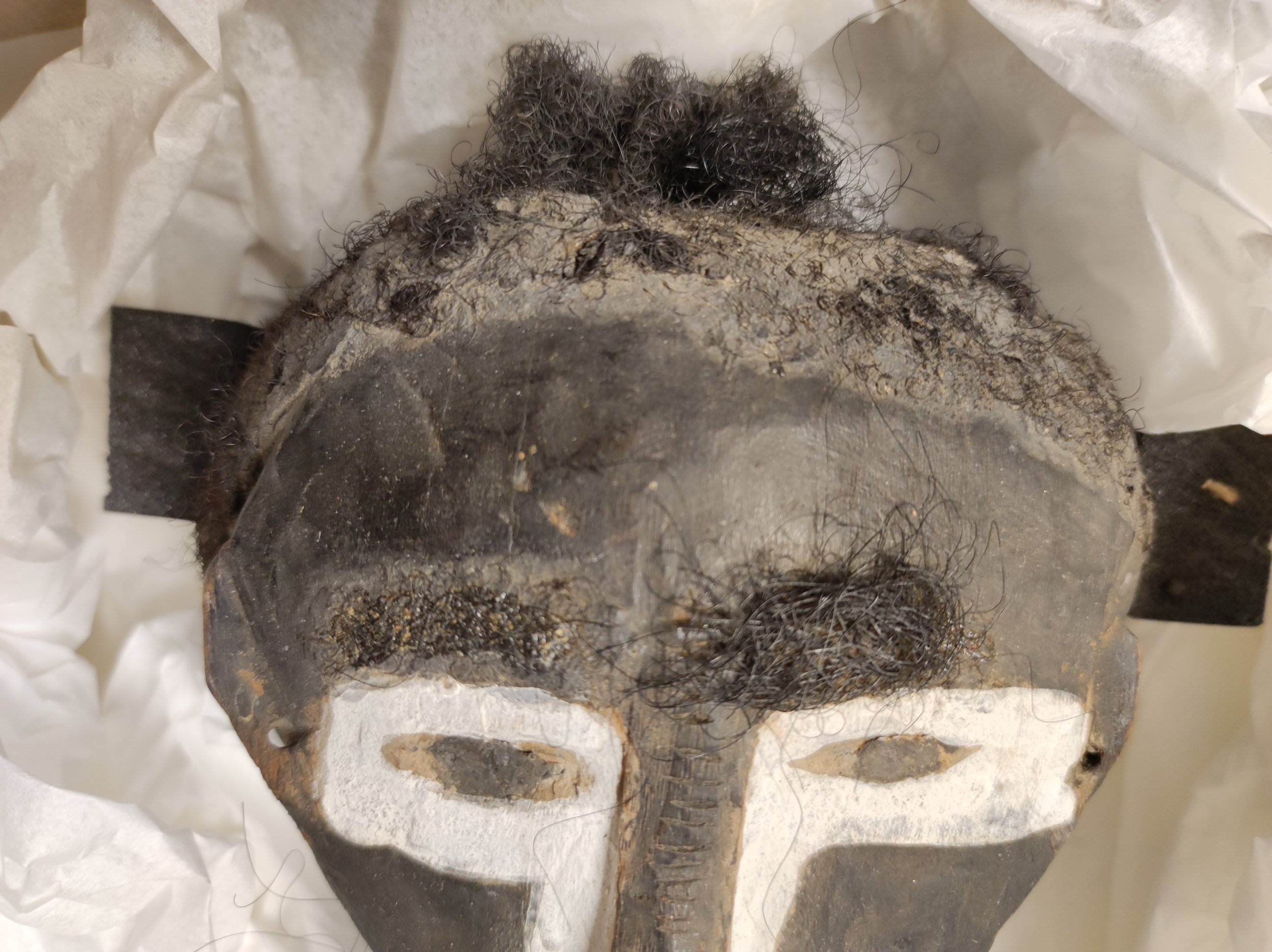

Figure from the Upper Congo © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Over half the book’s images portrayed the Bambuti’s ‘splendid’ dance performances, for next to hunting, “the pygmies' chief occupation is dancing… intimately connected with the chase” [2]. Harrison described the dancers “moving in and out, twisting and turning like a snake” while “every movement is executed in most perfect time” [3] accompanied by drums. He also refers to their ‘choruses’, which have since been categorized as multipart vocal arrangements, ranging from ‘The Spear Song’ and ‘The Animal Dance Song’ to ‘the Dance of the Honeybees’ when “everyone burst into the song of magic” [4].

Harrison also claimed that “when not dancing they are the most silent people possible, sitting for hours round their fires hardly speaking. As far as we could ascertain these people have no religion at all, having nothing which they worship or hold in reverence in any way” [5]. Yet he nonetheless seems to have acquired a wooden ‘fetish from the Upper Congo’, and his contemporaries also referred to Bambuti invocations to a ‘Higher Power’ and ‘Supreme Spirit’ [6], as embodied by the forest itself whom the Bambuti honoured with dancing and song.

Detail of the head of the wooden figure © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Yet for Harrison, such ‘dancing and song’ was simply the entertainment he wanted to bring to Britain for commercial purposes. So returning to Ituri territory in early 1905, he selected his ‘volunteers’, namely Chief Bokane, Matuka, Mafuti, Kuarke, Amuriape and Mongongu, who left their forest home on Harrisons’ pack donkeys. Progress was nonetheless slow, “as we had to lift them off and on nearly every quarter of a mile” [7] to avoid hazards. Harrison also reported that away from the forest shade “the women were always going off to sleep” and “had several tumbles in consequence”, so he “had to be most careful to travel them as much as possible out of the sun, for this knocks them over at once” [7].

Eventually reaching the Nile and then Egypt, the group spent a month in Cairo (see the author’s previous article parts I and II) before finally arriving in London on 1st June 1905, four days later making their debut at the Hippodrome theatre. Here reviews described their dancing accompanied by chanting and a ‘tom-tom’, although the effect of the resulting applause “was contrary to that intended, for the pigmies [sic] at once ceased their dancing” [8], apparently only performing when ‘the spirit moved them' [8] quite literally.

The six with manager William Hoffman photographed in London on 9th August 1905 by Sir Benjamin Stone MP who had recently photographed them in parliament. Image courtesy of © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Despite crass racism in sections of the press, “alleged savages and strangers from distant lands had a long history in Britain” [9], from the C.18th Polynesian visitor Omari received by George III to black servants working in grand houses. By the C.19th and early C.20th, minstrel shows and performers from Dahomey, Somalia and Jamaica entertained alongside counterparts from South Africa, Australia, India, China and the 'Wild West', with Harrison’s group part of the same continuum as ‘Farini’s Friendly Zulus’ and Egypt’s ‘Assuan [sic] Villagers’ [9]

Before long the group were taking tea with reporters, appearing in parliament, performing for royal guests at Buckingham Palace and dancing alongside military bands at the Yorkshire estate of Lord Londesborough. Making such an impression on Londesborough’s 12 year old nephew Osbert Sitwell, he later immortalized them as “a laughing prophecy of the jazz wind that would soon sweep the world”, echoing claims by one journalist who saw their ‘war dance’ as “the origins of the cake-walk” [10].

One of the group’s recordings of their ‘folk songs’ © Scarborough Museums & Galleries

Even creating “the first commercial recordings made by Africans in Britain” [11], the six toured and performed throughout 1906 and 1907, spending time at Harrison’s Yorkshire estate at Brandesburton where the villagers found them ‘unusual but pleasant neighbours’ [12]. They joined in songs at the local Sunday school, and made friends with the local children, with whom they played football. One child later recalled how ‘they used to run about here like normal and when I were [sic] ten they were aboot [sic] my size” [13], while others remember weeping with the group when they finally returned home to the Congo at the end of 1907.

About the author

Professor Joann Fletcher - is based in the Department of Archaeology at the University of York. She is also Lead Ambassador for the Egypt Exploration Society, patron of Barnsley Museums and Heritage Trust, and has been researching aspects of Scarborough Museums’ collection for over 20 years.

References

Harrison, J. (1905), Life among the Pygmies of the Ituri Forest, London, p.5.

Powell-Cotton, P. (1907), Notes on a Journey through the Great Ituri Forest, Journal of the Royal African Society 7 (21), p.6; ‘danced splendidly’, Harrison’s Diary VI 28.2.05.

Harrison (1905), p.18

Turnbull, M. in Rouget (2011), Musical Efficacy: Musicking to Survive - the Case of the Pygmies, Yearbook for Traditional Music 43, p.104-105; Turnbull 1992, Mbuti Pygmies of the Ituri Rainforest, Various Artists, SFW40401.pdf (si.edu)

Harrison (1905), p.22

Powell-Cotton (1907), p.5-6; Mukenge, T. 2002, Culture and customs of the Congo, London, p.58; Turnbull in Rouget 2011, p.103-104.

Harrison (1905), “we dare not risk them riding over rotten bridges or going up and down inclines”, p.23; “they cannot stand the sun”, Harrison’s Diary VI, 15.3.05.

The Era, 10.6.05, p.19 in Green, J. (1998), Black Edwardians: Black People in Britain 1901-1914, London, p.121; ‘the spirit moved them', Edinburgh Evening News 7.11.05, p.2, in Green (1998), p.129.

Green, J. (1995), Edwardian Britain's Forest Pygmies, History Today 45 (8), p.33-39; ‘Farini’s Friendly Zulus’ in Middleton, J. (2021), The Harrison Collection: Addressing colonialism in the collections of a Victorian big game hunter, Journal of Natural Science Collections 9, p.33.

Sitwell, O. (1952), Wrack at Tidesend, London; report from Scarborough Post 1.8.05, p.3, in Green (1998), p.126; ‘cake-walk’ in Birmingham Daily Mail 28.11.05 in Green (1998), p.130.

Green (1998) p.126-127; ‘Conversation between Bokani the Chief of the Pygmies and Mongongu the interpreter’ at Pygmies Conversation Between Bokani The Chief by Norient (soundcloud.com)

Green (1995), p.33-39; Sunday school in Gibbons, T. (2013), ‘The Pygmies who visited Edwardian England’, The Pygmies who visited Edwardian England - BBC News),

G.Watson in Green (1998), p.131, 137; photo by P.Calvert in Green (1998), p.132; T.Hagget later remarking Harrison “was only a little feller, not a deal bigger nor [sic] them”, Green, J. (2000), ‘A Revelation in Strange Humanity’: Six Congo Pygmies in Britain 1905-1907, Africans on Stage: Studies in Ethnological Show Business (ed. B. Lindfors), Indiana, p.180.