King Leopold II

By Erin Taylor

King Leopold II, King of Belgium, began to establish trading posts, roads and arrange treaties with chiefs in Central Africa in 1879. At the time, Leopold’s interactions with Congo were portrayed as the humanitarian efforts of an ‘eager’ philanthropist[1]. In reality, the events orchestrated by Leopold in Central Africa had catastrophic effects; the kind that would later be described by historian Adam Hochschild as ‘genocidal’[2].

Cartoon by British caricaturist 'Francis Carruthers Gould' depicting Leopold II of Belgium

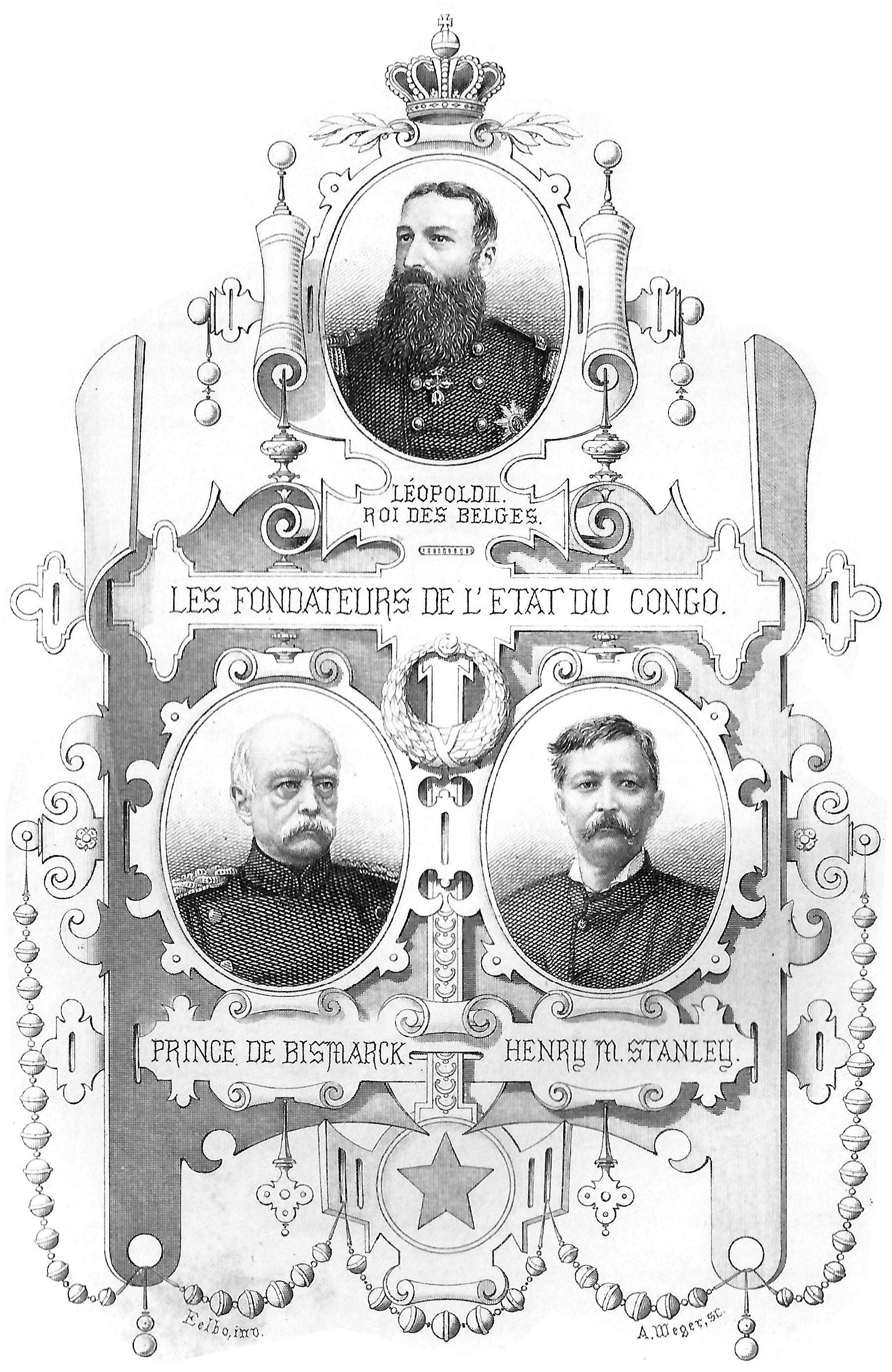

Leopold’s preparation for the invasion of the territory formally began in the Royal Palace, Brussels, where he hosted the Conférence de Géographie de Brux-elles from 12th to 14th September 1876[3]. Despite the Belgian government’s absence from European colonial efforts of the period, Leopold managed to convince the conference of ‘geographers, cartographers, explorers and military experts’ of his personal intent to ‘Christianise’, ‘civilise’ and ‘help’ the African communities[4]. During the conference, Leopold secured his position as president of the Association Internationale Africain. This association was established around his self-proclaimed values of fighting against slavery and introducing commerce to Central Africa[5]. The formal arrangements of the conference and establishment of the Association rendered Leopold’s plans in Africa official and paved the way for his commissioning Henry Morton Stanley to begin establishing the foundations of his rule within the territory in 1879[6]. By 1885, Leopold’s hold over Central Africa was secured under the Final Act of the Berlin Conference where Congo became recognised as falling under the jurisdiction of Association Internationale du Congo. Known as État Indépendant du Congo – ‘The Independent State of Congo’ - the territory was Leopold’s ‘sovereign political State’ and the world’s only private colony[7]. He had managed to convince the other European nations involved in the Berlin Conference of his humanitarian intent to civilise and had successfully distanced himself from suspicion of extractive and exploitative motivations.

Map of the Congo Free State by E. D. Morel. It shows the concessions of different rubber companies at his time.

Contrary to his promised plans, Leopold effectively transformed this vast territory into a ‘personal plantation’ for his own profit[8]. His primary interests were in ivory and rubber. In order to harvest ivory and farm rubber, the King of Belgium imposed forced labour upon the Congolese people. He set strict targets, called Rubber Quotas, which they had to fulfil[9]. When quotas were not met, or forced labourers attempted to flee, the King’s soldiers were instructed to shoot them and other punishments included mutilation and flogging[10]. Village populations decreased as Congolese families migrated elsewhere in resistance to Leopold’s efforts. Many of the forced labourers were worked to death while women were taken hostage and were often left to starve. Due to the conscription of the Congolese people to harvest rubber, there was little opportunity to hunt or farm to provide food for themselves and their families. This led to further starvation, vulnerability to disease, and left the population in a condition of ‘near famine’[11]. As a result of this, though the statistics are debated among historians, the population in Congo is estimated to have dropped significantly by 50% between 1890 and 1920[12]. Large expanses of land became depopulated as a result of these deaths and migrations, and the birth rate is reported to have been impacted[13].

Stamp of Congo Free State - 1886 - depicting King Leopold II

In the diplomatic arena, Leopold continued to claim he was helping the population of Congo despite the realities of his conduct and used strategies, such as awarding medals to individual allies, to harbour secure support[14]. However, by the early 1900s British and American protestant missionaries in Congo had started to shed light on the atrocities they had witnessed, and in response, Britain and America began to publicly condemn the actions of Leopold. Fearful that these revelations would tarnish the reputation of their own alleged ‘civilising missions’ elsewhere, many European nations put increasing pressure on Leopold to end his tyranny. Attempting to defuse the uproar, Leopold commissioned a report that he expected would testify in his favour. Contrary to his expectations, the report – published in November 1905 – confirmed the eye-witness testimony with regard to the reality of Leopold’s actions[15]. The Protestant missionaries sought the Pope’s support in ‘opposing the Congo administration’ but the Vatican ignored requests[16]. Nonetheless, the mounting pressure meant that in 1908, Leopold’s hold over Congo ceased and the Belgian state took over the administration of Congo. In exchange for the colony, the Belgian government provided the King with a large sum of money and he died a year later[17]. However, Leopold’s legacy remained, and the Belgian Congo continued to impose forced labour. Travaux d’ordre éducatif – ‘Obligatory Educational Labour’ was introduced in 1933 under the pretence that forced labour was ‘educating’ the Congolese, with violence often used to enforce the scheme. This legacy of violence and forced labour continued until the country’s independence in 1960[18].

About the author

Erin Taylor - is a second year BA History student at the University of Lincoln

References

[1] ‘Leopold II, Biography, Facts, & Legacy, Britannica’ Accessed 26 March 2022; Jairzinho Lopes Pereira, ‘The Catholic Church and the Early Stages of King Leopold II’s Colonial Projects in the Congo (1876–1886)’. Social Sciences & Missions 32, no. 1/2 (January 2019): 82–104, 83; ‘Henry Morton Stanley, Biography, Books, Quotes, & Facts, Britannica’. Accessed 11 April 2022.

[2] Hochschild, A. (1998) King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, New York.

[3] ‘Leopold II, Biography, Facts, & Legacy, Britannica’.; Lopes Pereira, ‘The Catholic Church and the Early Stages of King Leopold II’s Colonial Projects in the Congo (1876–1886)’, 85.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, 83.

[6] ‘Henry Morton Stanley, Biography, Books, Quotes, & Facts, Britannica’. Accessed 11 April 2022..

[7] Lopes Pereira, ‘The Catholic Church and the Early Stages of King Leopold II’s Colonial Projects in the Congo (1876–1886)’, 84.

[8] Weisbord, R. G. (2003) ‘The King, the Cardinal and the Pope: Leopold II’s Genocide in the Congo and the Vatican’, Journal of Genocide Research 5, no. 1 (March 2003): 35–45, 36.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.; ‘Leopold II, Biography, Facts, & Legacy, Britannica’. Accessed 26 March 2022.

[11] Ibid.

[12] ‘Leopold II, Biography, Facts, & Legacy, Britannica’. Accessed 26 March 2022.

[13] Weisbord, R. G. (2003) ‘The King, the Cardinal and the Pope: Leopold II’s Genocide in the Congo and the Vatican’, Journal of Genocide Research 5, no. 1 (March 2003): 35–45, 36.

[14] Ibid, 41.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid, 43, 44.

[17] Ibid, 44.

[18] Seibert, J. (2011) ‘More Continuity Than Change? New Forms of Unfree Labor In The Belgian Congo, 1908-1930’, Humanitarian Intervention and Changing Labor Relations Studies in Global Social History:7 (2011) 369-386, 369.; Victor Fernández Soriano, (2018) ‘”Travail et progrés”: Obligatory “Educational” Labour in the Belgian Congo, 1933-60’, Journal of Contemporary History 53:2, 292-314, 294, 311.