Scientific Racism

By Heather Hughes

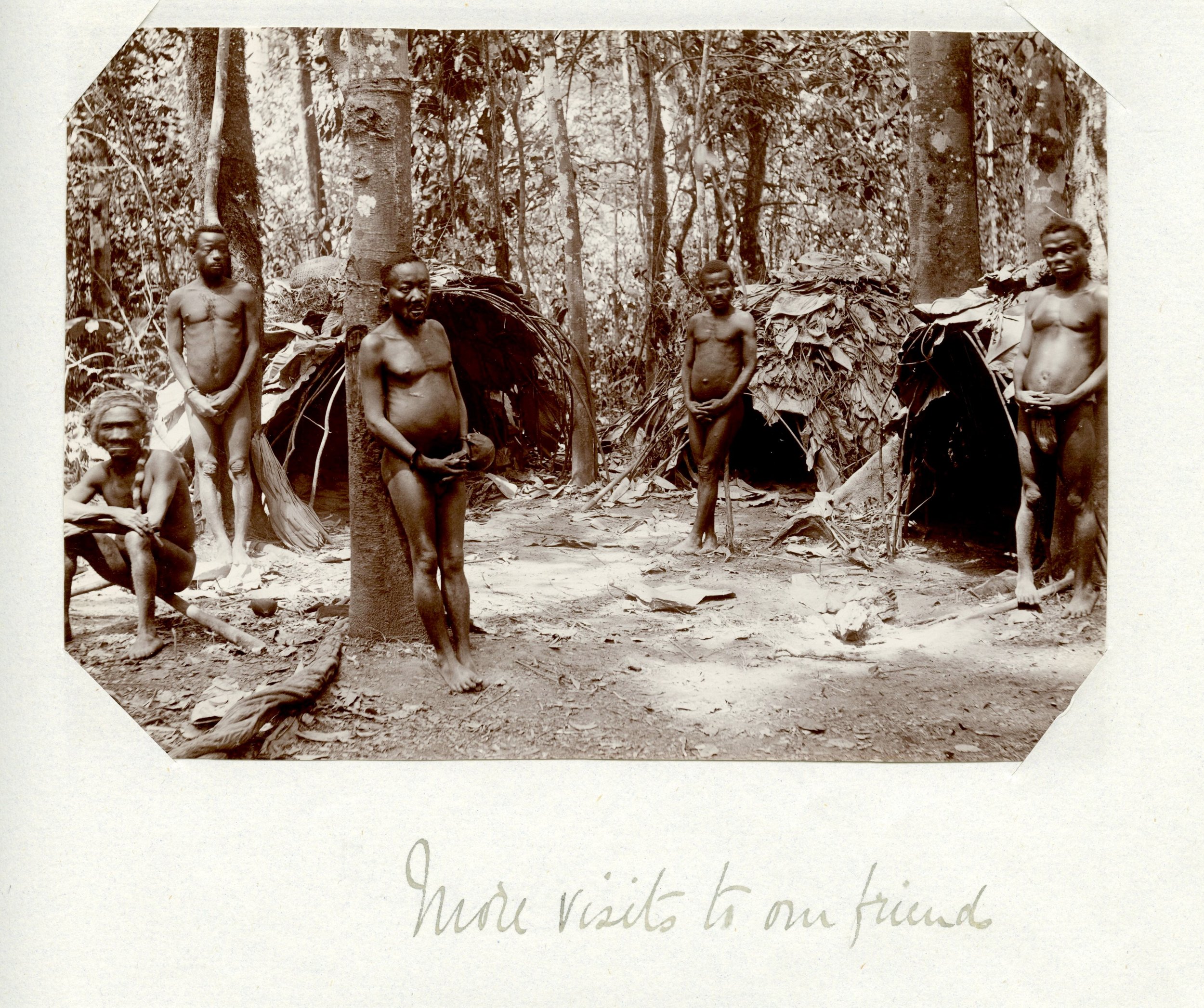

A few years before James Harrison first visited the Congo, another Englishman called Richard Cobden Phillips was living and trading at the mouth of the Congo River. In 1888, Phillips visited London to present a paper to the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. It was about the communities he had encountered along the river and on the Atlantic coast.

Richard Cobden Phillips (seated in the white suit and fez), with a group of visiting German anthropologists and some local children, probably early 1880s © Royal Geographical Society.

Phillips knew a reasonable amount about the peoples of this area: he had married a local African woman, Menina Bassa, and by the late 1880s they had three children. His paper was full of claims that were at the time thought to be ‘scientific’ observations about the culture and habits of African people. What were these claims?

Mafuti at the Anthropological Institute investigation in 1905, taken by W. and D. Downey © Scarborough Museums and Galleries [1]

First, said Phillips, the people were ‘primitive’ because of the climate, which was too hot and humid to allow civilisation to develop. He then proceeded to identify Africans as a human ‘type’, based on their physical appearance. He said they were generally shorter and more muscular than Europeans, their arms were proportionately longer and they could eat more food than Europeans. Phillips also claimed that Africans’ nervous system was stunted because they showed no reaction to pain. On the other hand, Africans could survive fever better than Europeans.

Most importantly for his argument, Phillips claimed that Africans were emotionally inferior: impulsive, ridiculous, quarrelsome, superstitious, unwilling to work, preferring to steal. Only the ‘better classes’ knew how to offer hospitality. Phillips did add that Africans’ sense of justice was very strong, but then confessed to be completely puzzled as to how this form of ‘development’ had come about, since the structure of African societies had remained unchanged from time immemorial.

Except, that is, for slavery. Phillips claimed that the slave trade had still been in full flow thirty years before, in spite of the British blockade to stop it. He acknowledged that the middle passage – the voyage across the Atlantic – had been ‘horrible’ but that the enslaved had better lives ‘under the civilised master than under the native’. The ending of slavery had caused impoverishment along the Congo coast, he said.

Bokane at the Anthropological Institute investigation in 1905, taken by W. and D. Downey © Scarborough Museum and Galleries

We can now recognise that these observations were shaped by a nineteenth-century European attitude that dehumanised African people and asserted that Europeans were the most superior ‘racial type’. Europeans believed that this superiority entitled them to use the wealth and peoples of Africa in whichever way they chose. And there was no need to reflect on how their presence in Africa as traders, explorers and invaders had disrupted Africans’ lives and shaped Africans’ reactions to them.

That attitude is what we call scientific racism. Learned societies such as the Royal Geographical Society and the Anthropological Institute supported and disseminated views like these. But they are now discredited. Modern research approaches, from history and archaeology to genetics and chemistry, have overturned the assumptions of scientific racism.

About the Author

Professor Heather Hughes - is Professor of Cultural Heritage Studies at the University of Lincoln. She trained as a historian at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London and has taught at universities in South Africa and the UK. Her research interests include biography writing and contested heritage. She currently leads Reimagining Lincolnshire, a public history project aiming to reinterpret the county's history in a more inclusive way.

References

1. Some of the six African 'pygmies' were subjected to investigations by the Anthropological Institute including anthropometric photographic poses, but no published report has been traced, in Green, J (1999) ‘A Revelation in Strange Humanity’: Six Congo Pygmies in Britain 1905-1907' in Bernth Lindfors (ed), Africans on Stage: Studies in Ethnological Show Business, pg 167. Bloomington: Indiana State University Press

2. ibid

3. Richard Cobden Phillips, (1888) ‘The Lower Congo: A Sociological Study’. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 17, pp. 213-237.