The Harrison Collection

Big game hunting is rightly frowned upon these days, but in the late 1800s it was viewed quite differently. Amongst the treasures held in our collections is an intriguing archive of a past time, The Harrison Collection.

Taxidermied jaguar believed to be from the Harrison Collection. © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

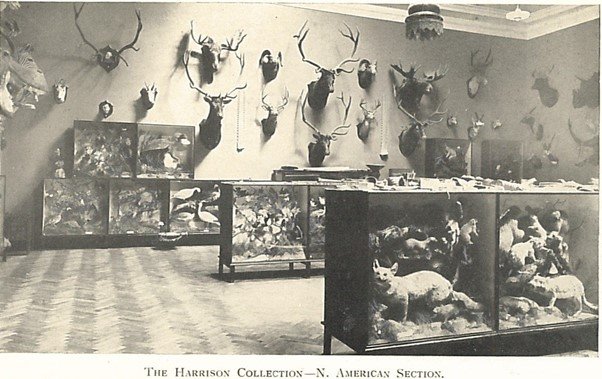

Some readers may be old enough to remember a time when the rooms above the library held a collection of stuffed animals and mounted game heads from all over the world. From elephants and giraffe to brown bear and moose, these were some of the hunting trophies of a gentleman hunter from Brandesburton called James Jonathan Harrison. Much of this collection has been lost as over the years the collection fell out of favour and was neglected, eventually moving from the Library to the then newly opened Woodend Natural History Museum, where there was little space to display much of it. Time had taken its toll, and lack of space meant much of what remained was kept in whatever space was available and suffered from damp and insect damage. All that remains of this collection are a few trophy heads, birds and a few stuffed animals including a jaguar from his trip to South America in 1885. What does remain though are a number of his travel diaries and hundreds of photographs, not only from his hunting trips around the world, but depicting a lost age of country house garden parties and even Caribbean picnics with future kings!

Colonel J J Harrison. © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

James Jonathan Harrison was born in Selby on the 8th of July 1857 to Jonathan Sables Harrison and his wife Eliza and was educated at Harrow and Christ Church College, Oxford. He was a volunteer in the East Yorkshire Regiment, but spent much of his time in the traditional country pursuits of the time, fox hunting and shooting. In 1885 he made his first hunting trip that we are aware of to South America. Although he later went on hunting trips to India, Japan and North America (returning via Bermuda where he partied with the future King George V), the majority of his hunting trips were to Africa.

From trips to South Africa and Portuguese East Africa (now Mozambique) and dining with King Menelik II in what is now Ethiopia, the place that seems to have drawn him most was the Congo. His first trip into the relatively unexplored interior of Africa was in 1904, to search for the recently discovered okapi. The existence of this shy, forest dwelling relative of the giraffe was brought to the attention of the scientific community by Henry Morgan Stanley who noted it in his journals in 1887. The first specimen was sent to London in 1901 and became something of media sensation.

In the gardens of Brandesburton Hall. © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

During further visits he befriended a tribe of indigenous people in the Ituri Rainforest and in 1905 brought a group of six back to the United Kingdom where these ‘Pygmies’ were toured around the country and displayed to paying customers in what was effectively a human zoo. This distasteful practice was interspersed with period of better treatment during their nearly three years away from home, and in his writings there is some evidence that Harrison had some respect for their way of life.

Harrison’s hunting trips show an insight into a way of life that has thankfully passed. At the time there were some truly barbaric land grabs in Africa and the indigenous peoples and wildlife were often seen as mere commodities to be exploited. Many museums have collections from our colonial past that are controversial and often glossed over or deliberately ignored. Although uncomfortable, these collections need to be discussed and seen in the context of their times, and the unspoken stories of the local peoples who made so many of these early missions of discovery possible need to be made available for study to redress misrepresentations of the past.

This article was originally submitted for The Scarborough News for Scarborough Museums’ regular Exhibit of the Week column. Date of original article unknown.