The Journey from Harrison to Paddington

By Yasmin Stefanov-King

In November 2014 Heyday Films; StudioCanal; TF1 Films Production; released the film Paddington, based on the books by Michael Bond [1].

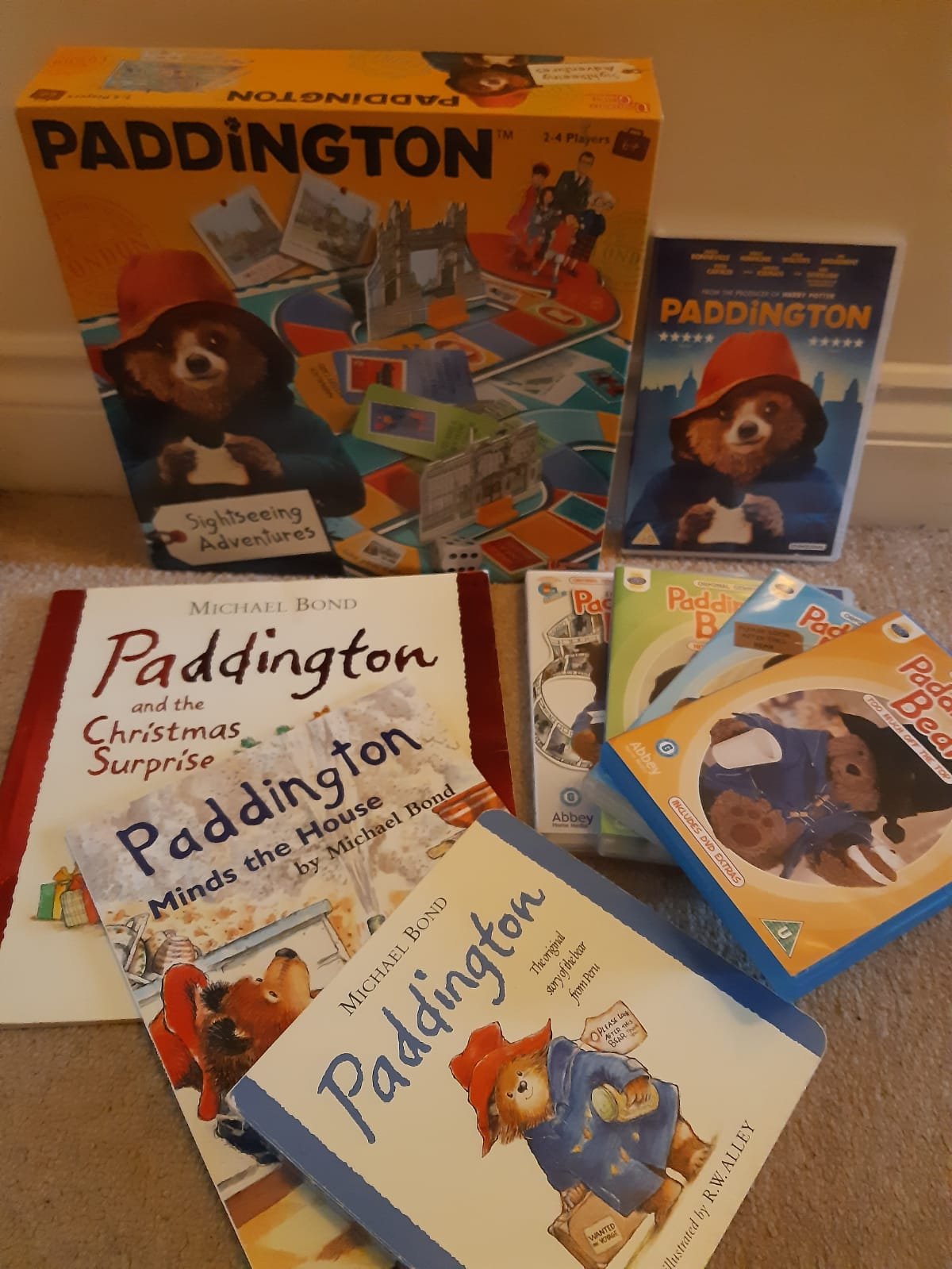

Collection of Paddington memorabilia [2]

The original stories were triggered by a lone stuffed bear, left on the shelves of a London shop on Christmas Eve 1956 [3], and a memory of child evacuees during World War 2 [4]. However, whilst the film touched on the theme of refugees in terms of the iconic “Please look after this bear” label, the main back story was much darker.

The idea was that a member of the British Geographical Society, Montgomery Clyde, whilst exploring ‘Deepest Darkest Peru’, came across an unknown species of bear. In accordance with explorers of the late 19th early 20th century, his instinct was to shoot, kill, and stuff the bear, and bring it back to England where it could have pride of place, and make him famous.

Original Paddington Bear jigsaw puzzle

Instead though, he discovers they can speak, teaches them the joy of marmalade, and leaves with the promise that should they ever come to England, then to look him up. He returns to England to face ridicule for his sentimentality in not bringing back a specimen, is banished from the British Geographical Society, and his family is destroyed. His daughter, Millicent Clyde, grows up to become a museum director, obsessed with collecting rare animals on which she carries out the taxidermy. When she hears about Paddington, her sole aim is to acquire him for the collection, and to have him displayed in a glass case on the stairwell.

This is a film, but the undercurrents of this approach to the world are absolutely reflective of the writings and behaviours of the time, and Harrison exemplifies this. Books of the time talk about ‘deepest, darkest Africa’ reflecting the Peru of the film. Those images of Montgomery Clyde, from his clothing to his attitude, are based on the behaviours of the explorers who went out into the world, determined to acquire a sample of everything they possibly could, and if it was rare, or dangerous, then so much the better.

The N. American section as shown at Scarborough Library. Image courtesy of © Scarborough Central Library

At that time, photos were not enough, there needed to be the actual creature. But as can be seen with the Harrison collection, what happens when you bring all these things home? Suddenly that creature is taken out of context, removed from its own story, and placed in the proverbial glass case, just like Millicent Clyde wanted for Paddington.

The issue as well is that with a collection such as the Harrison one, there comes a time when fashions change, and the idea of a room full of the stuffed bodies of once living animals starts to feel a little uncomfortable. So it may be that those collections are donated to museums, as happened here at Scarborough. As fashions change those animals get boxed away, stored until they are needed, and their stories are lost forever. A Paddington that is never looked after.

However, this is the thing that is different about the Harrison collection. Harrison did go around shooting huge numbers of animals before choosing the best examples and getting them stuffed, but he also did something else, he wrote about it. Initially that may not seem something to be seen as a positive, but the major difference between the Harrison collection and many others, is that those diaries give life to the animals. Instead of just being yet another stuffed head on the wall, or bear in a glass case, the diaries provide a depth to the stories.

Harrison wrote on Saturday, December 2nd, 1899.

Extract from Harrison’s diary © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

“Up at 5.45 and away at 6, having hired 10 kraal camels to help us along a day's march. I turned off to hunt along the foot hills; after 3 miles spooring lesser koodoo I suddenly saw a tail sticking out of a large hole in ant heap. Seeing some animal I got my shikaree to push in a stick, further in at a side hole, when out came an ant eater which I promptly shot - a wonderful bit of luck, as very few people have ever seen them, much less shot them.”

The collection then includes his photo of the poor aardvark, as well as the complete animal in its taxidermied form.

Image of the aardvark from the Harrison Collection. © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

The aardvark mentioned in the diary, and from the photo - now stuffed and part of the Harrison collection © Scarborough Museums and Galleries

Should the animal have been shot and killed in order for it to be stuffed and displayed? Of course not, but at least here it is given that back story, a reason for its existence within the collection, more than just a small white card with a date and Latin name on it. Suddenly these animals have a new lease of life, a chance to hear their stories told again. Paddington would be happy, and Millicent Clyde? Absolutely furious.