Understanding the Colonial World View Through Children’s Books

By Jane Gill

The publication of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland in 1865 is said to have been the starting point for a ‘golden age’ of children’s literature which lasted into the beginning of the 20th century, the time of Harrison’s expeditions. This was a book written just for children, for their enjoyment rather than their education. However, at this time, access to books such as ‘Alice’ was usually limited to the upper and middle classes and reflected ideas and themes with which they may have been familiar. While public libraries had begun to open in the middle of the 19th century, literacy levels were still low among the working classes. However, these rose following the introduction, in 1880, of compulsory education for children between 5 and 10 years old.

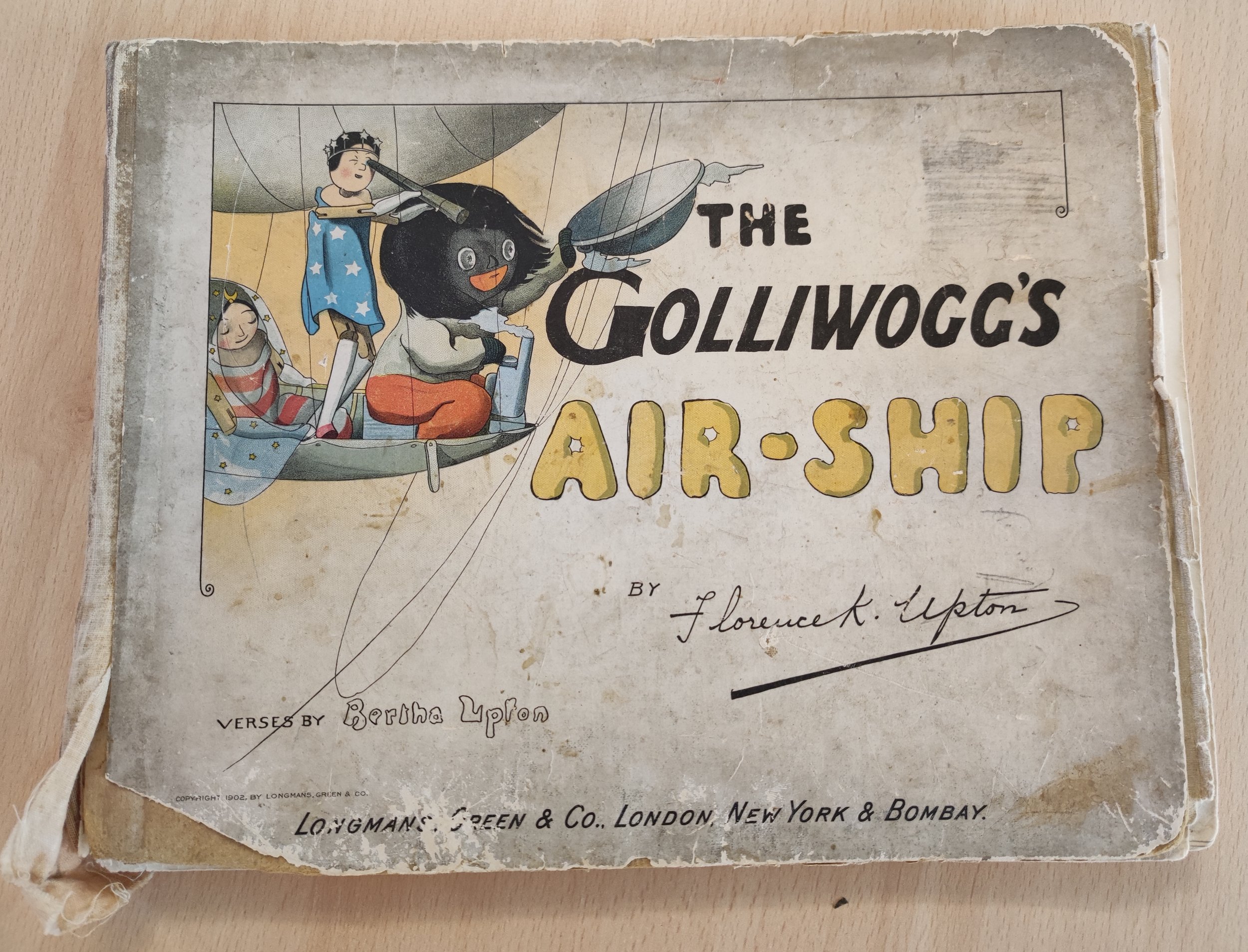

Front cover of Upton’s 1902 publication “The Golliwogg’s Air-ship”

At this time children’s views of the world were limited; they clearly did not have access to the media and travel opportunities which are accessible to today’s children. Their knowledge was constructed from their own experiences and then, as they became more available and literacy levels rose, from the books to which they now had access. In the 1890’s these books included Upton’s (1895) depiction of golliwogs in The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and Bannerman’s (1899) The Story of Little Black Sambo. Here the characters are portrayed as caricatures which feature exaggerated physical characteristics, such as eyes, lips and hair, but perhaps of greater concern, is how they are portrayed as either figures of “fear and darkness” (Dixon, 1997:96) or simple, child-like characters, grinning and seemingly happy to be in service to others. This is particularly concerning, especially when considering the child reader’s limited view of the world at that time. It is shocking, then, that these characters continued to appear in a range of children’s books until the 1970s, notably by Enid Blyton in the Noddy books (Dixon, 1977).

Front cover of Blyton’s 1968 “The Three Golliwoggs”

Front cover of Hodgett’s 1954 book “Toby Twirl Tales No. 8” which includes “The Lost Piccaninny”

Children’s literature, then and now, provides what Bishop (1990) describes as “mirrors, windows and sliding glass doors” and each have an important part to play in developing a child’s view of the world. Through the mirror, children can see their own life reflected; it can be familiar and safe. The window allows children to look through and see a different picture, something with which they may not be familiar, lives lived differently to theirs. The sliding glass door allows a child to be drawn into the experience of the book, stepping through into the world of the story, whether in their imagination or through taking action.

Bishop (1990) recognised the importance of children seeing themselves in the mirror provided by the book but advised caution – should a child only see their own ‘reality’ reflected, they may get an “exaggerated sense of their own importance and a false sense of what the world is like”. When considering the impact of children’s literature in the first Golden Age this should be born in mind. However, it is surely important to recognise that what is seen through the window may have been manufactured to present a particular world view.

Children’s books published in the first golden age give children a glimpse through the window into a world based on coloniser / colonised power relations. While books published at the time of Harrison’s travels such as The Little Princess (Burnett, 1905) and The Secret Garden (Burnett, 1911) may have acted as a mirror to a few readers, for others they may have provided a constructed view of India from the perspective of the coloniser, with which they may otherwise have been unfamiliar. Similarly, Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses, published in 1885, was a popular book and would have been read by many children who could relate some of the poems to their experiences. However, they may also perpetuate the idea of the colonial power as superior in all ways to anyone whose life is seen through the window. Stevenson’s “Foreign Children” has been criticised by, among others, Traver (2019) for the depiction of these children as: “Little Indian, Sioux, or Crow, Little frosty Eskimo, Little Turk or Japanee,…” and it seems clear that this language would not be used in the 21st century. The line which follows these is “Oh don’t you wish that you were me?” which suggests that the child narrator sees their own life as superior to that of the “Foreign Children”. Some editions of A Child’s Garden of Verses are now published without this particular poem, reflecting the challenges of relating the attitudes of the 19th century to contemporary understanding and sensibilities.

Harrington (2016) recognises the value of the of books in offering children a window through which they can see an accurate portrayal of contemporary life in other countries, suggesting that this can support a developing cultural awareness. However, while it should clearly be accurate, different perspectives may mean that what is accurate to one person’s experience may be problematic to another. Contemporary picture books, such as Handa’s Surprise (Browne, 1994) depict a child’s experience of life in rural Kenya which is vastly different to that of a child living in the slums of Kibera.

So the portrayal of people of different races in children’s literature is still worthy of care and consideration. Now, as in Harrison’s time, it is clear that what we read, and the images we see, have an impact on us and on our understanding of the world. As Harrison’s collection is evaluated in a very different century it may be that we also need to reflect on how children develop their understanding of the world – perhaps through exploring Harrison’s collection and other artefacts from different times and places.

About the author

Jane Gill - has been a university lecturer in Early Years and Education for the past 12 years, but more importantly worked within the early years sector for 25 years. A tireless advocate for children's literacy, her passions are children's literature and immersive theatre.

References

Bannerman, H. (1899) The Story of Little Black Sambo. Grant Richards.

Bishop, R.S. (1990) Mirrors, Windows and Sliding Glass Doors. Perspectives: Choosing and using books for the classroom. 6(3).

Browne, E. (1994) Handa’s Surprise. Walker Books.

Burnett, F.H. (1905) The Little Princess. Charles Scribner.

Burnett, F.H. (1911) The Secret Garden. William Heinemann

Carroll, L. (1865) Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. MacMillan.

Dixon, B. (1977) Catching Them Young: Sex, race and class in children’s fiction. Pluto Press.

Harrington, J. (2016) We’re all kids: picture books and cultural awareness. The Social Studies. 107(6), 244-256.

Traver, T. (2019) “But I wouldn’t Want My Son to Read It:” Adapting A Child’s Garden of Verses for a New Millennium. Literature and Film Quarterly.

Upton, B. (1895) The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls. Longmans, Green and co.